There was once a thriving Black middle class based on farm ownership. But during the twentieth century, the USDA helped erase that source of wealth.

The office of civil rights at the Agriculture Department is located on the third floor of a building named after a white supremacist. The Jamie Whitten Building, named in 1994, honors a member of Congress who started his career by eliminating a federal agency because its studies encouraged “racial intermingling” and ended it by referring to Mike Espy, a Black member of Congress and future secretary of agriculture, as “boy.” Whitten’s prejudices were reflected in the policies he supported: floods of cash for wealthy white farmers and next to nothing for Black farmers.

The representative from Mississippi never worked for USDA, but as chair of the House Appropriations subcommittee on agriculture for over four decades, he exercised so much control over the department’s budget that he became known as the “Permanent Secretary of Agriculture.”

In a “typical year” in the 1960s, writes historian James Cobb in The Most Southern Place on Earth, Whitten secured $23.5 million for wealthy farmers who made up 0.3 percent of his district—and just $4 million in food stamps for the 59 percent of his district that lived below the poverty line. He once explained to Senator George McGovern that if “hunger was not a problem, [n-word]s won’t work.”

While Whitten was less abashed in his racism than many of his fellow lawmakers, they were no less committed to defending rich white farmers. From the start of Whitten’s political career to the present, lawmakers in both parties have set their differences aside to send the exceeding majority of federal funds to commercial farmers, almost all of them white men.

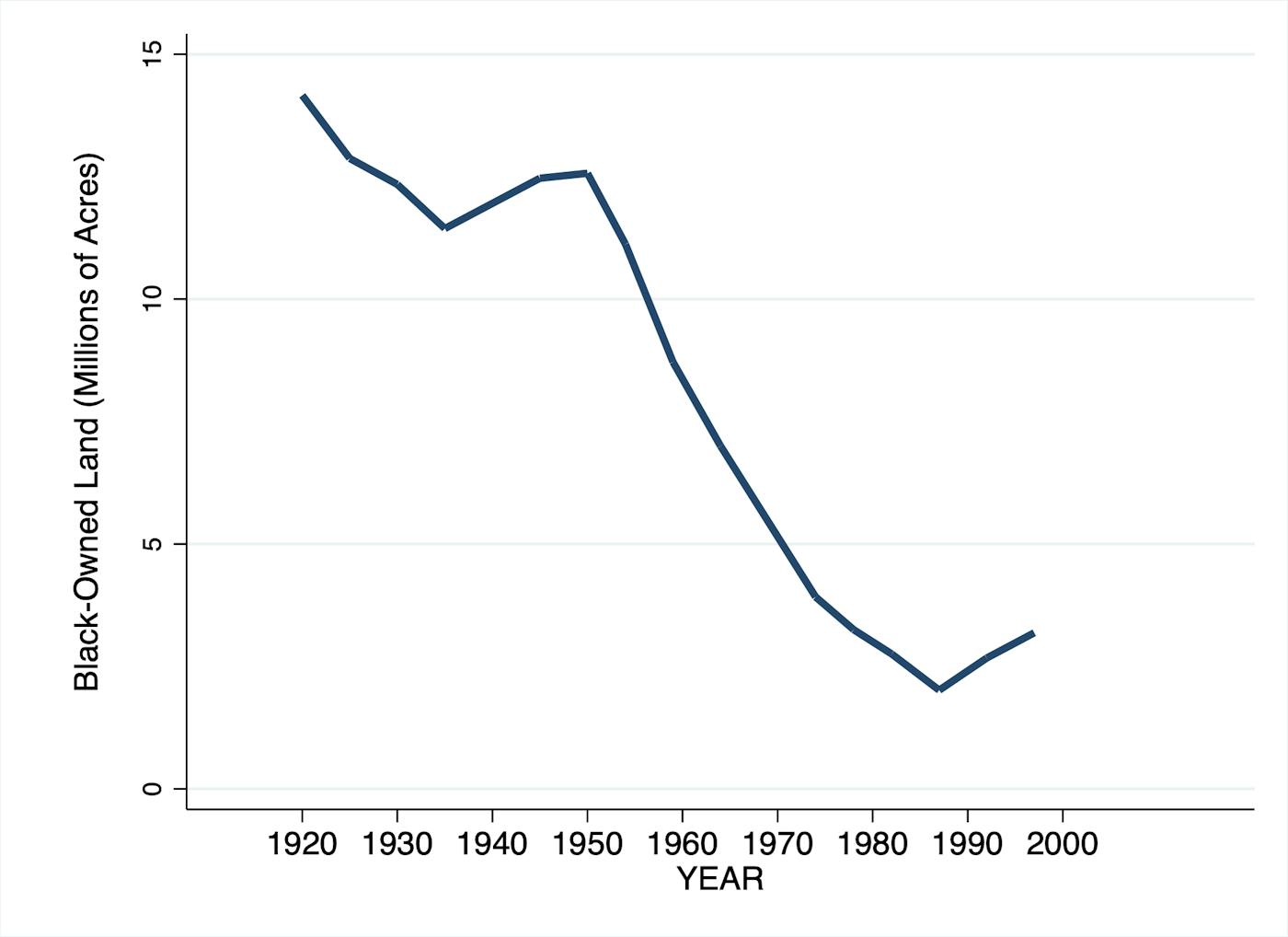

Black farmers not only lost out on these massive subsidies—they have been effectively disenfranchised within the modern agricultural system. Under conditions of savage oppression, Black families emerged in the early 1900s with almost 20 million acres of farmland and “the largest amount of property they would ever own within the United States,” according to the historian Manning Marable. Since then, they have lost roughly 90 percent of that acreage.

Despite the scale of this deliberate, state-sanctioned dispossession, no one has estimated how much Black families lost. For the first time, in a forthcoming paper to be published in the American Economic Association’s Papers and Proceedings journal, our team conducted a comprehensive analysis of historical data from 1920 to 1997 and found that the lost wealth and income from the land totals about $326 billion—roughly the size of Hong Kong’s annual gross domestic product. This enormous loss not only cost the families who saw their land and dreams taken from them, but destroyed a rural Black middle class that had, by sheer will, emerged in the aftermath of slavery. Since family wealth is iterative—growing slowly at first, adding to itself, and accumulating and expanding over time—this blow to a nascent Black middle class has reverberated down the generations.

What happened

The Civil War destroyed the basis of wealth in the Old South—slavery—and with it a system of social relations. In their struggle to create a new society, amid universal oppression and disadvantage, Black families acquired property at an astounding rate.

By 1890, about 20 percent of Black farm families owned their land, and by 1910 that figure had reached 25 percent. Even as white creditors cheated them, white planters worked them ragged, white politicians disenfranchised them, and white mobs targeted them with arsons and lynchings, over 425,000 Black families were able to save enough to purchase almost 20 million acres in the Jim Crow South. The number of people in these families roughly numbered the total African Americans who migrated north in the first Great Migration, and the acreage they owned approached the size of South Carolina.

This rural Black middle class was the hope of a generation. W.E.B. DuBois—who completed several extensive studies of Black farmers in the early twentieth century—numbered 200,000 farmers among 250,000 Black “independents” in America, so-named for their economic power. “Landowning farmers and entrepreneurs,” writes historian Debra Reid, “reorganized rural society by founding fraternal societies and building schools, churches, and businesses to cater to a black clientele.”

In his study of a rural county in Alabama, the sociologist Charles Johnson found that farm owners had larger, better quality homes; more equipment and livestock; kept their kids in school longer; grew more food for themselves; and had more magazine subscriptions than non-farm owners. Other writers found similar results in North Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, and elsewhere in the South.

/ Free Pick of the Week: Homeland Security’s New Disinformation Board Is a Bad Idea, Just Not for the Reason Tucker Carlson Says It Is.

Numerous descendants of Black farm owners have used the leg up to build better lives for themselves, and many of those who stayed on the farm used their independence from the white power structure to advocate for civil rights in the middle of the twentieth century.

These landowners provided refuge and support for civil rights activists who assisted local people as they campaigned for political rights in the 1960s. “What really is important about how the movement was able to take root in Mississippi [is] there was a network of Black landowners,” Bob Moses, a key civil rights figure, said in a recent documentary. “This was really our secret weapon.”

Yet the federal government acted against these families. Hard-pressed as they were already, the modern agricultural system created as part of the New Deal was the single greatest cause of the decline of Black farmers. As Ira Katznelson makes clear in When Affirmative Action Was White, New Deal liberals needed Southern legislators to pass their agenda, which gave the South’s elite immense control over legislation. These elites were determined to maintain the South’s racial order and moved as a bloc to crush any program that threatened it.

Unable to draft legislation that discriminated explicitly on race, Southern policymakers instead drafted laws that discriminated by scale.

These lawmakers attacked programs for small farmers, like those run by the underfunded and short-lived Farm Security Administration, for turning Black farmers into “lazy, thriftless loafers” and for being “un-American” and “communistic.” As U.S. Representative Harold Cooley of North Carolina explained at a hearing in 1943, subsidies for large farmers were “money earned” for “the benefit of the general welfare,” while Farm Security Administration programs for small farmers turned the recipients into “ward[s] of the government.”

As politicians killed assistance for Black farmers, they established enormous financial programs for the planter class many of them had emerged from. The government initiated massive subsidy programs in this era—federal payments went from 3 percent of farm income in 1929 to 31 percent in 1940—and almost all of the money went to wealthy white landowners. Southern legislators, wary of federal bureaucrats interfering with their region’s racial order, ensured that these new agricultural programs and dollars would be managed locally, under white control.

In 1934, an anonymous correspondent from Arkansas warned the readers of The Crisis, the NAACP’s magazine, that New Deal policies would spell the end of Black farmers. Almost all the state’s Black-owned farms, “the whole [life] savings of from one to three generations,” would be “swept off the map” unless “the colored people can get some of the Government set-up as well as the others.… If one could help in this it would do Negroes nearly as much good as the Civil War.”

As planters started to receive large payments not to plant, they evicted their tenants, invested in labor-saving machines, and started to reap profits that would make it impossible for most Black farmers to compete. By the 1950s, the modern agricultural system was in place in the South, and Black farmers would see their farmland decline by four million acres in the next decade.

Around the same time, Black farmers became targets in the white backlash to the civil rights movement. After Brown v. Board, when the courts indicated that they would no longer reflexively defend segregation, Southern white politicians and elites—fearful that their Black constituents would threaten their power—took any measure they could to defend their positions, which included taking advantage of USDA’s power in the still heavily agricultural South.

As policymakers continued to fund industrialized agriculture, the founder of the Citizens’ Council drew up a plan in 1956 to remove 200,000 African Americans from Mississippi over the decade by way of “the tractor, the mechanical cotton picker … and the decline of the small independent farmers.”

“The situation for rural blacks was bad enough before the Brown decision,” writes Pete Daniel, a historian whose book, Dispossession, covers this era. But afterward, “USDA programs were sharpened into weapons to punish civil rights activity.”

USDA agents refused loans to Black farmers, interfered in elections for county committees that distributed federal funds, restricted the crops Black farmers could grow, and sometimes participated in outright theft. William Strider, a USDA agent in Mississippi, would delay paying out operating loans to Black farmers who had posted their land as collateral to his friend, Norman Weathersby. Weathersby required Black farmers to put up their entire farms as collateral for loans to purchase farm equipment, so when the USDA farm operating loan failed to come through, and the farmers missed their payment to Weathersby, he acquired the farmland. An AP report found that Weathersby acquired over 700 Black-owned acres in this way.

Black farmers understood “technology” and “land consolidation” were not to blame for their circumstances: “The removal of Negroes from land ownership in the South,” wrote a black farmers’ organization in 1966, “is part of a conscious policy to destroy the political power of the black vote.” Black farmers lost two-thirds of their remaining acreage between 1950 and 1974.

Black farmers still say that the government decided to enact policies and enable discrimination that dispossessed previous generations of their land. In a letter to Senator Elizabeth Warren, sent during the 2020 Democratic presidential primary, a group of Black farmers called for “something very simple, something that white farmers in this country have enjoyed for more than a century. We want a department that works for us, not against us.” “Technocratic adjustments” and “audits,” they said, were not enough to make up for the intense discrimination they had faced.

“The disaster we suffered was unnatural,” says Will Muhammad, a Black farmer in Alabama. “We were assaulted by white folk.”

Resistance

Even in an era of USDA vote-fixing and intimidation, the white establishment blamed impersonal “economic forces” for Black land loss. A front-page article in The New York Times in 1965 announced that Black farmers were “doomed” because of “economic threats” like the “mechanical tobacco harvester” and an unexplained “lack of capital.” One expert predicted that Black farmers would be gone in 10 years, while another gave them a little over two decades to “virtually disappear.”

The Times forgot to mention that the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights had released a major report earlier that year that concluded there was “unmistakable evidence that racial discrimination has served to accelerate the displacement and impoverishment of the Negro farmer.”

Black farmers were well aware of this discrimination. Despite being excluded from the modern credit system, owning few resources, and having little public support, they banded together to keep their land.

Civil rights leader and former sharecropper Fannie Lou Hamer is known for her run for Congress in the 1964 Democratic primary, a race where she challenged Jamie Whitten. Hamer also helped raise funds for Black farmer organizations and started a cooperative named Freedom Farm in the Mississippi Delta. Her 680-acre operation was one of hundreds of Black-led cooperatives founded in the late 1960s and ’70s that helped slow the dispossession of Black families.

In 1967, a group of 22 of these cooperatives came together as the Federation of Southern Cooperatives to pool resources and preserve Black farmland. As Joe Rosenberg Johnson told Jet in an interview that year about his Alabama cooperative, “We don’t have the conservation service experts testing our land. We don’t have the bankers lending us money. We don’t have the Agriculture Dept. giving us help, loans, or information. But we’re pulling together now.”

By 1977, the FSC included more than 130 cooperatives and approximately 30,000 member families. The organization, which still serves cooperatives and Black farmers today, saved millions of dollars’ worth of Black-owned farmland. Through this work, the group defied mainstream accounts of Black land loss as the inevitable result of mechanization and “progress,” and of Black farmers as “less sophisticated” than white landowners.

The house that Jamie built

The FSC and similar groups won critical victories, but they still worked in the shadow cast by the USDA. Even as the civil rights movement made progress in the 1960s, Jamie Whitten ensured that the department’s powerful white supremacist bureaucracy remained untouched.

As head of a key House committee, Whitten used his influence over the budget to control USDA offices and staffing. Under President Dwight Eisenhower, he killed a research agency because of its studies on economic and racial disparities in rural areas. When John Kennedy’s administration sought to replace it with a new agency, the Economic Research Service, Whitten secured a promise that the new division would not publish studies on Black farmers, farmworkers, and other marginalized groups—a promise that successive administrations also kept. Under President Lyndon Johnson, Whitten unilaterally killed the Great Society’s rural poverty office by defunding and absorbing it into a more conservative part of the department.

The “Permanent Secretary” cut staff from projects he disliked, while he secured political appointments for friends and cronies. Orville Freeman, Johnson’s secretary of agriculture, told reporters that he had “two bosses. One is President Johnson. The other is Jamie Whitten.”

Whitten successfully institutionalized his vision of aristocratic racial hierarchy at the USDA. He was famous for attacking “hound dog projects”—that is, any program he thought might help Black Southerners. He killed food programs, studies of Black sharecroppers, and even a small program to help Black workers learn how to drive tractors.

FARM SECURITY ADMINISTRATION, 1940

Meanwhile, with his blessing, the department not only sent almost all its loans to wealthy, white farmers, it even guaranteed millions in loans to suburban swimming pools and segregated country clubs—including Whitten’s own. Since his influence over the department’s offices, staff, and work was so sweeping, it is no surprise that Black farmers still know the USDA as “the Last Plantation.”

The Commission on Civil Rights confirmed pervasive discrimination at the department in two major reports, one in 1965 and another in 1982. White outlets gave these reports little coverage at the time, as they continued to claim “land consolidation” and technology were to blame for the decline of Black farmers.

A 1990 congressional study concluded that “little [had] changed” at the department since the 1982 report and that the USDA continued to “implement policies … directly responsible for the loss of land and resources” of Black farmers. The USDA’s response was to adopt the rhetoric of equal rights, writes the historian Pete Daniel, while systematically denying rights to Black families in practice.

In 1997, Black farmers sued for widespread discrimination at the department between 1981 and 1996. (The USDA had no civil rights office from 1983, when President Ronald Reagan effectively closed it, to 1996, when President Bill Clinton restored it.) Although the farmers won a settlement in the case—called Pigford v. Glickman—the payments did little to relieve the enormous debts many Black farmers held or to help them get their land back. After a bipartisan but erroneous narrative took hold—repeated everywhere from Breitbart to The New York Times—that the settlement was rife with fraud, many Black farmers were left off worse than they were before, their white neighbors resentful against them and legislators in Congress unwilling to offer help. And most Black farmers had already lost their land by the 1980s, making them ineligible for relief under Pigford.

Although Obama-era officials claimed Pigford helped bring a “new era for civil rights,” business proceeded as usual at the USDA. The Government Accountability Office released six reports documenting patterns of discrimination at the USDA between 1999 and 2009. One independently commissioned study found ongoing discrimination against minorities within the department in 2011. A wide-ranging investigation by two of us found rampant deception and discrimination throughout the Obama years. Reports from current employees and Black farmers indicate that little changed under President Donald Trump.

The cost

When the federal government undertook to assist white Southerners in the dispossession of Black-owned farmland, it succeeded in destroying a significant share of Black wealth. Black families lost at least 14 million acres after 1910. We estimate that the portion lost between 1920 and 1997, along with the lost income from that land, would be worth around $326 billion today. If this amount were distributed across all Black families, their median household wealth would nearly double, from $21,000 to $37,000.

FARM SECURITY ADMINISTRATION, 1939

We developed this estimate based on records from the Census of Agriculture. We looked at acreage owned over time, applying adjustments for undercounts of Black farmers. We used land values in the census to assess the value of lost land, then applied an interest rate based on historical returns to farmland to get our final estimates.

These estimates are conservative in some important ways. Many Black farmers once owned land in what are now some of the most fertile areas of the country, where farm returns have long been much higher than what we used in our estimates. Developers have turned some of this land, like in Hilton Head, South Carolina, into incredibly expensive residential and commercial properties. We also did not account for land lost before 1920. As the historian John C. Willis documented in Forgotten Time, two-thirds of farm owners in the Mississippi Delta were Black in 1900, but that share had fallen to less than one-fifth by 1910.

Neither does our estimate account for Black families’ lost investments in their children’s education, their diminished political rights, their lost self-determination and autonomy, their lost dreams, hopes, aspirations, and way of life. No calculation could ever account for these things.

But our estimate sets a starting point for reckoning with the way that federal policy undercut what was once the single largest source of Black wealth. This land loss explains a significant role in the enormous Black-white wealth gap. That gap is more than 10 times larger than the income gap between Black and white families; even white high school dropouts have twice as much average wealth as Black college graduates.

This racial chasm has its origins in numerous government policies—the general exclusion of Black veterans from the G.I. bill, political disenfranchisement, widespread denial of home loans, failure to enforce equal hiring, mass incarceration—and in merciless white violence against Black people, including reprisals against organizing agricultural workers and farmers in the Leflore Massacre of 1889 and the Elaine Massacre of 1919. One pattern we see throughout history is that when Black Americans make relative progress the white establishment comes in and takes it away.

Last year, Congress passed debt relief for anyone from a “socially disadvantaged group” who had certain types of loans with or guaranteed by the USDA’s Farm Service Agency. Before the Agriculture Department disbursed any of the money, a Florida judge froze the program in response to a lawsuit brought by a white farmer backed by a powerful conservative legal fund.

Black farmers and their advocates criticized the USDA for not getting the money out faster. “We’re probably not even going to get it,” Lloyd Wright, a Black farmer and former director of civil rights at the Agriculture Department, told The Guardian last year. “They could have done it within weeks. They were aware some angry people were trying to stop it. I think we’ll get the debt relief around the same time we get the 40 acres and a mule.”

The year Jamie Whitten retired, Congress named the USDA’s headquarters after him. When he died the next year, in 1995, Bill Clinton said he had “worked tirelessly on behalf of America’s farmers” and “never gave up working to build more opportunity for all Americans willing to make the most of their lives.”

Whitten’s work lives on. In 2018, just 2,900 farms in Mississippi received over $170 million in soybean subsidies while Mississippi farmers, as a whole, received $363 million in subsidies and payments. The average commercial farmer in Mississippi has a net income of $396,000, according to the 2017 Census of Agriculture. Meanwhile, the 20 percent of Mississippians living below the poverty line, 587,000 people in total, received only $7 million in payments from Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or what remains of welfare. Mississippi’s farmers are 86 percent white, and its TANF recipients are 84 percent Black. The “Permanent Secretary” is dead. Why do we still have his policies?